March of 1934 ushered in the first post-prohibition celebration of St Paddy’s. It had been fourteen years since America’s Irish immigrants celebrated properly. When the drought finally lifted, many a bootlegging entrepreneur made a quick leap into the gambling rackets. And those who’d already been juggling both enterprises thickened what they had in motion. Facilitating the shift, the timeline seemed to offer an almost seamless transition.

Early in 1931, in an effort to counter the ill effects of the Great Depression, Nevada re-legalized gambling. And if women weren’t happy with their husbands’ new vocation, the state made it a little easier to cease matrimony that same year. Come 1933, the rest of the country seemed to wise up as well. Right around the time legislators canned the Volstead Act, voters ruled in parimutuel wagering—better known as “playing the ponies.” Though not the first California track to open, Santa Anita Park was one of the state’s most popular. The track welcomed sportsmen at the tail end of 1934, roughly one year after the final day of prohibition.

Despite repeal and a new gambling boom, some bootleggers refused to give up the craft that easy. And with such a hefty investment on equipment, raw materials, and with a paying clientele still demanding product, why would they? One week after the joyous 1934 St Paddy’s celebration, an “investigator disguised as a cowboy” stumbled upon something hidden in the Mojave desert—“four column stills, sixteen 9,000 gallon vats, an immense boiler, and other equipment.” Rather than making a bust, authorities instead chose to stake the spot out, and before long they got movement. After tailing a truckload of alcohol leaving the plant for a few miles, they overtook the vehicle, arresting four men and taking in 750 five-gallon cans of bootleg alcohol. But lawmen were after more than just the drivers.

After a bit of digging, the list of the accused tallied all the way up to seventeen. Quite a hefty outfit for just one liquor cache. Agents sought out C. L. Wright, the owner of the land the still perched on, and five other men who’d since been identified as “officers” of a wholesale grocery that records highlighted as suppliers. They had the right—and usual—suspects. What agents stumbled upon was an operation that, for more than a decade, manufactured and delivered shipments of bootleg hooch throughout the Southland, and even trucked product into Northern California and areas of Nevada. The previous “heads” of this illicit sugar ring had recently retired—involuntarily—but apparently the business was still active.

Proclaiming his innocence, Frank Borgia had been in court for over a year, desperately fighting to stay out of prison. Eventually he’d end up serving a four year stretch at McNeil Island for moving sugar and for cheating tax men. Borgia’s partner in the LA sugar caper—the owner of the original wholesale company that supplied sugar, yeast, and metal cans to the Southland’s unregistered liquor stills—was a man by the name of George Niotta. Following a bitter falling out with Frank Borgia, Big George left the bootlegging trade for the legal end of the liquor business. Getting situated in NorCal before the repeal, he purchased San Francisco’s newly opened, El Rey Brewing Company. Interestingly, investigations uncovered that the still raided shortly after St Paddy’s had been receiving its sugar via rail from that very same city.

In the absence of Frank and Big George, authorities believed the sugar ring had ceased to exist, but apparently it hadn’t. In fact, two of the men they now sought—John Cacioppo and Tony Bruno—were actually lower level players who’d recently received a promotion. George Niotta’s son-in-law, Johnny Cacioppo, and Johnny’s younger brother Gaspar, got their start in the sugar ring as teenagers back in 1924. Behind the wheel of supped up Fords, they’d been out-driving “dry agents” ever since. On the other end of the business, brothers Tony and Sam Bruno maintained the still sites and cranked out a finished product. The Cacioppos picked up what the Brunos fashioned. The absence of leadership in the final year of “the drought,” however, had spurred a change.

With newer hands to drive and distill, Johnny and Tony now ironed out logistics. Like the earlier “managers” of the outfit, Tony’s brother Sam also made an unwanted exit. Sam Bruno was “serving a life sentence for the kidnapping of two truck drivers, whose cargo of liquor he and associates attempted to hijack.” Bootlegging could be—and often was—a dangerous and bloody endeavor. Strengthening this claim, 1934 is the same year L.A. courts legally declared the deaths of four ranchers and fruit vendors who’d gone missing—Tony Buccola, Frank Baumgarteker, Joe Porazzo, and Joe “Strong Man” Ardizzone. Each of them was heavily involved in the bootlegging trade.

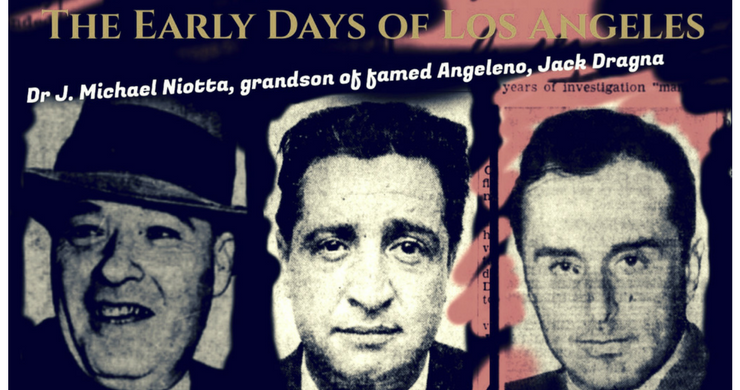

Although the raid following St Patrick’s Day looked to be the final play of the bootleg gang, more action soon followed. That summer, officers nabbed the head of the illicit ring. On June 12th, U.S. Marshalls hauled in Jack Dragna on transportation of un-taxed liquor, and in July they arrested his longtime associate, Eddie Dragna. Though the charges pending against Jack were later dismissed, tax men would continue to hound both Dragnas for unpaid taxes on unregistered stills for the next two decades to come.

Read more about outlaw entrepreneurship on the West Coast in J. Michael Niotta’s true crime debut, The Los Angeles Sugar Ring, and look for more LA teasers from Niotta’s newest project, an early history of organized crime in Los Angeles co-authored with longtime mafia researcher, Richard N. Warner.

- The Walnut Bust: The Early Days of Los Angeles With Dr J. Michael Niotta - May 21, 2020

- The Cornero Gang & the Infamous Page Brothers: The Early Days of Los Angeles With Dr J. Michael Niotta - June 4, 2019

- The Man From Chicago: The Early Days of Los Angeles With Dr J. Michael Niotta - December 12, 2018