Being stuck at home might be giving you itchy feet, so you’re probably looking for somewhere to go once this covid mess is over. Nowadays thanks to the Internet, people are more aware of how they can travel while being kinder to people and the planet: don’t ride elephants in Thailand! Don’t fly unless you have to (I’m guilty of this)! But how about when your idyllic Mediterranean getaway is secretly run by a shadowy group of slippery psychopaths?

Most people know about the Mafia from The Godfather, or any Robert De Niro flick. Don’t get me wrong, I love The Godfather — it has great acting, cinematography and an iconic score — but so does Game of Thrones, and no-one takes it for a blow-by-blow account of what happened in medieval Europe. The Mafia is real, and for people in Southern Italy it’s something they have to live with every day.

I met Edoardo on the steps of the Teatro Massimo, the famous Palermo opera house, the steps of which Sofia Coppola once graced with her direful dramatics in The Godfather Part III. Edoardo’s a member of Adiopizzo, a grassroots movement that aims to oust the Mafia from Sicily. As well as more extravagant misdeeds like kickbacks and drug trafficking, the Mafia charges a pizzo, or ‘tax’, on businesses in their territory.

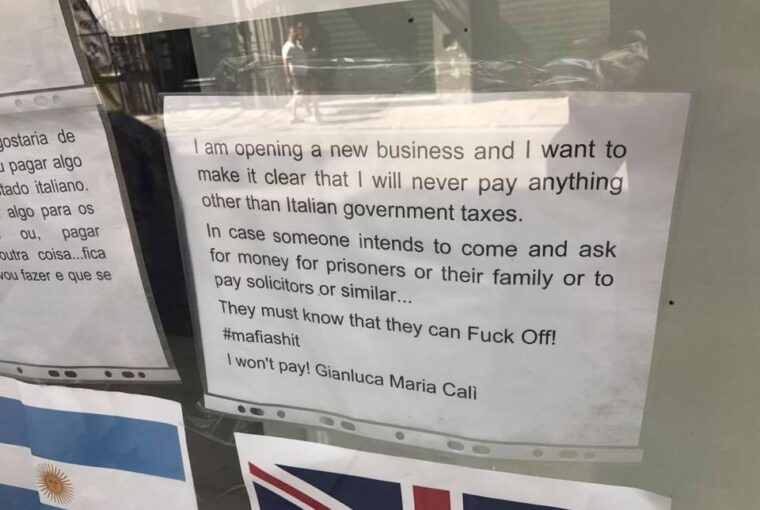

“Addiopizzo began as a small group of young people who had no experience of the Mafia,” said Edoardo. “It all started one night in 2004 when we were dreaming about opening a pub in Palermo. So we sat down to make a plan, and one of our friends put pizzo under expenses. It’s pretty normal in Palermo if your pub is successful for someone to come knocking on your door.”

The pizzo serves two roles. First of all, it’s a way of reminding those lowly commoners who’s in charge. Secondly, it’s a way of making money and a little extra change to pay off the lawyers. But mafiosi don’t always ask for cash – for example, the godfather could ask you to hire his dim-witted nephew or stock his favourite brand of coffee. Refusing could lead to unfortunate mishaps, such as being firebombed or shot four times in the head, as happened to businessman Libero Grassi in 1991.

“We peppered the town with stickers – ‘a people that pays pizzo is a people without dignity’,” Edoardo recalled. “The idea was to make people aware we have a common problem. People were scared because of what happened to Libero Grassi. Some of the shopkeepers even ripped off the stickers. But there’s no need for any one person, a hero who they can kill – if a lot of people do a little thing, that’s far more effective.”

They can firebomb one store, but they can’t firebomb them all. We passed a shop selling coppola flat caps, like the kind Al Pacino wears in The Godfather. In the window was an orange Adiopizzo sticker.

“Everyone thinks the coppola is the hat of the Mafia, but really it’s the hat of the Sicilian peasants,” said Edoardo, “so we’re trying to take that back! The Mafia approached him with the typical method, stuck glue in his keyhole, but the owner called Adiopizzo and asked for a lot of stickers! The sticker is a promise not to pay, and to go to the police.”

By signalling they’re no pushover, the idea is threatening them becomes more trouble than it’s worth. And by supporting these businesses, you can make it more profitable to run a Mafia-free business than one which pays the protection racket.

“Recently there was a case with ten Bengali merchants by the train station,” Edoardo said. “They were in an especially vulnerable situation because they were immigrants, and the Mafia would rob them because they thought they wouldn’t go to the police. But they decided enough is enough.”

Adiopizzo helped out too.

“We assisted them from the very beginning to the end of the trial. First we softly approached them and gained their trust. Then we encouraged them to report everything to the police. Our lawyers prepared them for their testimony, and Addiopizzo was by their side in the trial as plaintiff.”

In the end, nine mobsters were arrested for assault, extortion, arson and robbery.

We walked through more streets and alleys as Edoardo showed me around squares, plaques and other places associated with the Mafia until eventually we reached the Palermo Cathedral. Sicily’s been plundered and invaded by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Napoleon, and this cathedral, a repurposed mosque, was an interesting mix of Arab-Norman style. This is where Father Pino Puglisi is buried. Pino was an anti-Mafia priest who lured kids away from a life of crime in his rough Palermo neighbourhood. In 1993, hitmen shot him point-blank in the neck on his 56th birthday. His last words were said to his killers with a smile: “I’ve been expecting you.”

For the longest time the Italian establishment didn’t want to admit the Mafia exists in the first place. When they did, they said it was something like Johnny Depp in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies: some sort of quaint, misunderstood tradition. The Church played along too, since in the Cold War those godless commie heathens were a greater threat. But now the attitude towards the Mafia’s changing and people see it for what it is: a murderous web of corruption. In 2013, Father Puglisi was beatified by the Pope himself, who condemned mafiosi as evildoers.

“If he becomes a saint, that will really send a message because these people pretend to be religious,” Edoardo said.

We walked out onto the Piazza Magione, a wide open square that was the childhood home of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino. The two judges, who grew up playing football here amongst the rubble of bombed-out Palermo, weren’t scared to go for the guilty verdict in a Mob trial, and they paid for it with their lives. A roadside bomb blew up Falcone, his wife and three bodyguards in 1992, and his childhood friend Borsellino a few months later. Now a tree stands in the square in their honour.

Just behind it lay a playground where a group of children were playing. It was paid for by members of Adiopizzo.

“The Mafia collects money and use it for themselves. With the same money, voluntarily, we use it to do something good,” Edoardo said. “It makes me feel good to see these children playing.”

Just then, we heard some commotion round the corner. People stepped out of their shops and cafes and clapped as a large crowd marched down the street, holding up banners of Falcone and Borsellino and little red notebooks. After a car bomb blew him up outside his mother’s house, the little red book in which Borsellino kept all his notes mysteriously disappeared from the crime scene.

“Resistenza, resistenza!” they chanted.

After top boss Totò Riina was arrested for Falcone and Borsellino’s murders, his gang went to war with Italy itself, bombing the Uffizi art gallery (killing five people, including a nine-year-old girl) and Milan (killing three firefighters, a cop and an innocent bystander) as a way to put pressure on the government to back off. Many of the marchers believed Borsellino was digging up dirt on powerful members of the Italian government, and a deal was struck between police, politicians and Cosa Nostra.

“It’s really frustrating because every year a little bit comes out, but we always have to wait a little bit more,” said long-haired fellow, who’s refused to cut his hair or shave his beard until the killers of his son, Antonino Agostino, a cop, and his pregnant wife, are brought to justice.

While conspiracy theories are all the rage right now thanks to Trump, this one’s not entirely cuckoo. In 2018, a top-ranking politician with close ties to Silvio ‘Bunga-Bunga’ Berlusconi, three dirty cops and several mafiosi were convicted for having organised the ‘State-Mafia Pact’.

I was getting hungry, and Edoardo dropped me off to the Antica Foccaceria street food restaurant. Established in 1834, it’s older than Italy itself, but in 2007 it also drew the attention of the Mafia, who demanded a 50,000 euro payoff. They broke into customer’s cars and tried to sabotage food supplies. The brothers who ran the joint were scared they’d lose the business so they went to the carabinieri. A local boss was arrested, and one brother even testified in court. It was the first time since Libero Grassi that someone did something so bold. Better pizzo-free pizza than pizza-free pizzo, amirite?

The Mafia’s held Sicily in its clutches for over a century and a half, keeping it poor and stagnant and murdering anyone who stood in its way (and then some). But by supporting Adiopizzo, you can help put the squeeze on the wiseguys. They’ve got a website and an app to let you find businesses which refuse to pay protection money and help you book tours on the island. Of course, our morbid fascination with bad guys will never go away, so kind of like the Pablo Escobar tours in Colombia you can’t really blame people for their curiosity. After all, that’s what brought me here. So Adiopizzo organises its own tours, where you can meet some of the victims and see where everything went down – Falcone’s murder, the real-life Corleone family.

If there’s something Italians don’t skimp on it’s a snack, and I gorged myself like Action Bronson at an all-you-can-eat buffet. It was a long day and when I wandered outside it was already dark but plenty of families were out, chattering away outside the bars and cafes. It was time to order a cold one. That was an offer I couldn’t refuse.

- Adiopizzo: Anti-Mafia Movement in Sicily - July 28, 2020